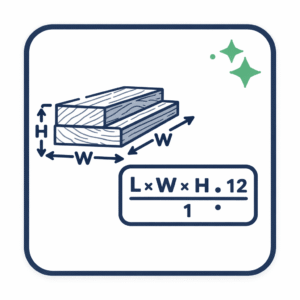

Foundational Constraints and Numeric Targets

Two immutable quantities set the baseline requirement for any dunk attempt:

- Official rim height: 10 feet (120 in; 3.048 m). See Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/story/why-are-basketball-hoops-10-feet-high.

- Athlete standing reach: fingertip height when standing flat-footed with the dominant arm fully extended. This measurement is the single most important anthropometric input to a standing reach vs rim calculator or a dunk reach predictor tool.

The simple arithmetic used by public calculators is:

required_vertical_to_dunk = rim_height + chosen_clearance - standing_reachchosen_clearance accounts for hand size, ball diameter and the type of dunk (rim touch, one-hand, two-hand, windmill). A conservative coaching convention is 6–11 in for a one-hand finish and 10–12 in for a two-hand finish; advanced stylistic dunks often require still greater clearance to permit manipulation. A rim clearance calculator basketball or jump height needed to dunk estimator should allow the user to choose the clearance value appropriate to their technique.

Mechanics: How Vertical Impulse Is Produced

The vertical jump is the product of three interacting mechanical subsystems:

- Force capacity — maximal force an athlete can apply to the ground (largely a function of strength and muscle cross-section).

- Rate of force development (RFD) — how quickly force can be expressed; Olympic-style lifts and ballistic work preferentially increase RFD.

- Stretch-shortening cycle efficiency — the ability to harvest stored elastic energy during the eccentric phase and convert it to concentric force (improved by reactive plyometrics).

These components are visible in the jump phases: approach, penultimate step, final step, takeoff (force production), flight (ball control), and landing. Practical coaching focuses on increasing ground reaction impulse (force × time) while simultaneously shortening ground contact time in reactive work where appropriate.

Approach and Penultimate Step Mechanics

Approach mechanics convert horizontal momentum into vertical impulse. The penultimate and final strides orchestrate a controlled lowering of the center of mass and prepare the limbs to apply force upward. Coaches emphasise a lengthened penultimate step followed by a shortened final step to create optimal takeoff positioning. See technical discussion: https://simplifaster.com/articles/better-long-jump-technical-models/.

Key measurable coaching cues for the approach:

- rhythm and tempo so the athlete achieves a consistent penultimate–final step ratio;

- control of hip height on the penultimate step to allow force application in the final step;

- foot placement and angle at the final contact to maximise vertical force vector.

Takeoff and Upper-Body Contribution

At takeoff the athlete should synchronise hip extension, knee extension and ankle plantarflexion to maximise vertical impulse. An effective arm swing raises whole-body momentum and contributes to impulse: coordinated arm-drive increases peak power available at takeoff, enabling more initial upward velocity. For dunkers the arm action has two additional functions: it improves vertical displacement and positions the ball for an efficient finishing motion.

Training emphasis for the takeoff:

- triple-extension drills (hip/knee/ankle) with unloaded and light-load jumps;

- resisted sprint start work to rehearse explosive hip extension;

- medicine-ball throws that replicate the upward trajectory and timing of hand release.

Flight, Ball Control and Finishing Mechanics

Flight time is short even for elite jumpers—most successful dunks have flight times under one second—so the athlete must use that interval efficiently to position the ball and finalise hand placement. The physical relation between vertical jump height h and total hang time T is derived from basic kinematics and is commonly used by practitioners who measure jump by flight time: T = 2 * sqrt(2 * h / g) (g ≈ 9.81 m/s²). This formula underpins many consumer measurement tools that calculate hang time for dunk from measured flight time. See a practical explanation: https://www.topendsports.com/testing/products/vertical-jump/video.htm.

Finite technical details for the finish:

- hand positioning: the dominant hand must be able to control the ball above the rim; athletes who can palm the ball reliably need less clearance;

- wrist action and elbow drive: for a one-hand dunk the elbow drives down and through the plane of the rim to create a downward force on the ball; for two-hand finishes both shoulders and elbows must clear and stabilise the ball;

- contact with the rim/ball: a soft, controlled finishing stroke reduces the chance of rim hang or injury.

Typical Dunk Types and Mechanical Demands

- Rim touch / fingertip tap — baseline task; required vertical equals rim height minus standing reach. Useful for early testing with a standing reach vs rim calculator.

- One-hand dunk (tomahawk/tip-over) — moderate clearance (6–11 in) and strong single-arm control; requires less palmability if clearance is higher.

- Two-hand dunk — higher clearance (~10–12 in) and bilateral coordination; typically more stable but demands greater peak vertical.

- Windmill/360/complex rotations — require extra clearance for arm sweep and rotation; these moves increase the required vertical by ~8–16 in depending on the athlete.

Coaches and athletes can translate these demands into numeric targets using a dunk training target calculator, vertical jump to dunk calculator or basketball dunk vertical estimator which combine standing reach, chosen clearance and measured vertical to report readiness.

Drills and Progressive Training

A systematic progression converts physical qualities to dunk capability. A practical sequence:

- Baseline measurement — record standing reach and CMJ (countermovement jump) or approach vertical using a validated device. Use readings in a calculate dunking ability from reach tool. See measurement reliability literature: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5377563/.

- Strength block (4–6 weeks) — heavy squats, Romanian deadlifts, single-leg strength work to raise maximal force.

- Power conversion (4–6 weeks) — loaded jump squats, trap-bar jumps and Olympic derivatives to increase RFD.

- Reactive/technical block (4–6 weeks) — progressive plyometrics, approach rehearsals and simulated dunk finishes. Use a dunk reach predictor tool to monitor progress.

- Peaking and conversion — reduce volume, maintain intensity, practise full approaches and contest-specific scenarios.

Evidence supports measurable improvements with structured plyometric and combined training: meta-analyses report moderate effects on countermovement jump height. See Stojanović et al., PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27704484/.

Measurement, Monitoring and Practical Calculators

Regular testing is essential. Practitioners use:

- CMJ and approach vertical tests to quantify capacity; many teams publish combine schedules and measurements: https://www.nba.com/stats/draft/combine.

- Flight-time derived calculators to convert hang time to estimated jump height and compare with a standing reach vs rim calculator.

- Specific web tools such as a vertical jump to dunk calculator, rim clearance calculator basketball, jump height needed to dunk, calculate hang time for dunk, calculate dunking ability from reach, dunk training target calculator and basketball dunk vertical estimator all use the same physics and anthropometry; their output depends on the accuracy of input values and the chosen clearance parameter.

Be cautious with consumer devices: measurement error exists when flight time alone is used without force-plate validation. Use the same device and protocol for repeat tests to maximise reliability.

Injury Mitigation and Session Management

Dunking places large eccentric loads on the lower limb and stresses the shoulder when finishing. Mitigation practices:

- progressive volume increases for plyometrics (avoid sudden spikes);

- technical rehearsal of landings and body alignment;

- shoulder stability work for repetitive finishing;

- scheduled deloads and data-driven readiness monitoring.

Final Considerations

Dunking is a measurable target that combines anthropometry, mechanical production and precise motor skill. Use a validated testing protocol to obtain standing reach and vertical measures, then set a numeric target with a required vertical to dunk calculation (rim height + chosen clearance − standing reach). Convert that target into a phased training plan that develops strength, power and reactive mechanics while rehearsing approach timing and finishing technique. Regular measurement—CMJ, approach jump and controlled dunk attempts—allows the coach to update the dunk reach predictor tool or basketball dunk vertical estimator inputs and keep progress incremental and safe. Evidence from meta-analyses shows structured plyometric and combined interventions produce moderate improvements in jump height; applied coaches should integrate those modalities with careful technical drilling so physical gains become reliable dunking performance.

Selected references and resources:

- Britannica — Why are basketball hoops 10 feet high? https://www.britannica.com/story/why-are-basketball-hoops-10-feet-high

- Stojanović E., et al., “Effect of Plyometric Training on Vertical Jump Performance” (meta-analysis). PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27704484/

- TopendSports — Calculating vertical jump using video/flight time: https://www.topendsports.com/testing/products/vertical-jump/video.htm

- Measurement reliability for flight-time methods: Attia A., et al., “Measurement errors when estimating the vertical jump height.” PMC: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5377563/

- Simplifaster — Better long-jump technical models (penultimate step): https://simplifaster.com/articles/better-long-jump-technical-models/

- NBA Draft Combine (measurement procedures and historical results): https://www.nba.com/stats/draft/combine